The scientific community stands at a crossroads in defining our current geological era. While we officially remain in the Holocene epoch that began 11,700 years ago, a growing body of evidence suggests humanity has fundamentally altered Earth’s systems to such an extent that we may have entered an entirely new geological epoch—the Anthropocene. This proposed epoch, derived from the Greek words “anthropos” (human) and “cene” (new), represents more than just scientific taxonomy; it embodies a profound reckoning with humanity’s role as a geological force comparable to volcanoes, glaciers, and tectonic shifts.

The debate carries implications far beyond academic circles, touching the core of environmental policy, economic systems, and our collective responsibility as planetary stewards. Yet despite compelling evidence of human impact, the scientific establishment recently rejected the formal recognition of the Anthropocene as an official geological epoch, highlighting the complex intersection of scientific rigor and political implications inherent in this discussion. stratigraphy

Understanding the Anthropocene Concept

Scientific Foundation and Timeline

The term “Anthropocene” entered scientific discourse in 2000 when atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen and biologist Eugene Stoermer proposed it to describe our current geological interval. However, the concept has deeper roots, with similar ideas traced back to 1922 when Russian geologist Aleksei Pavlov appears to have first suggested the term.

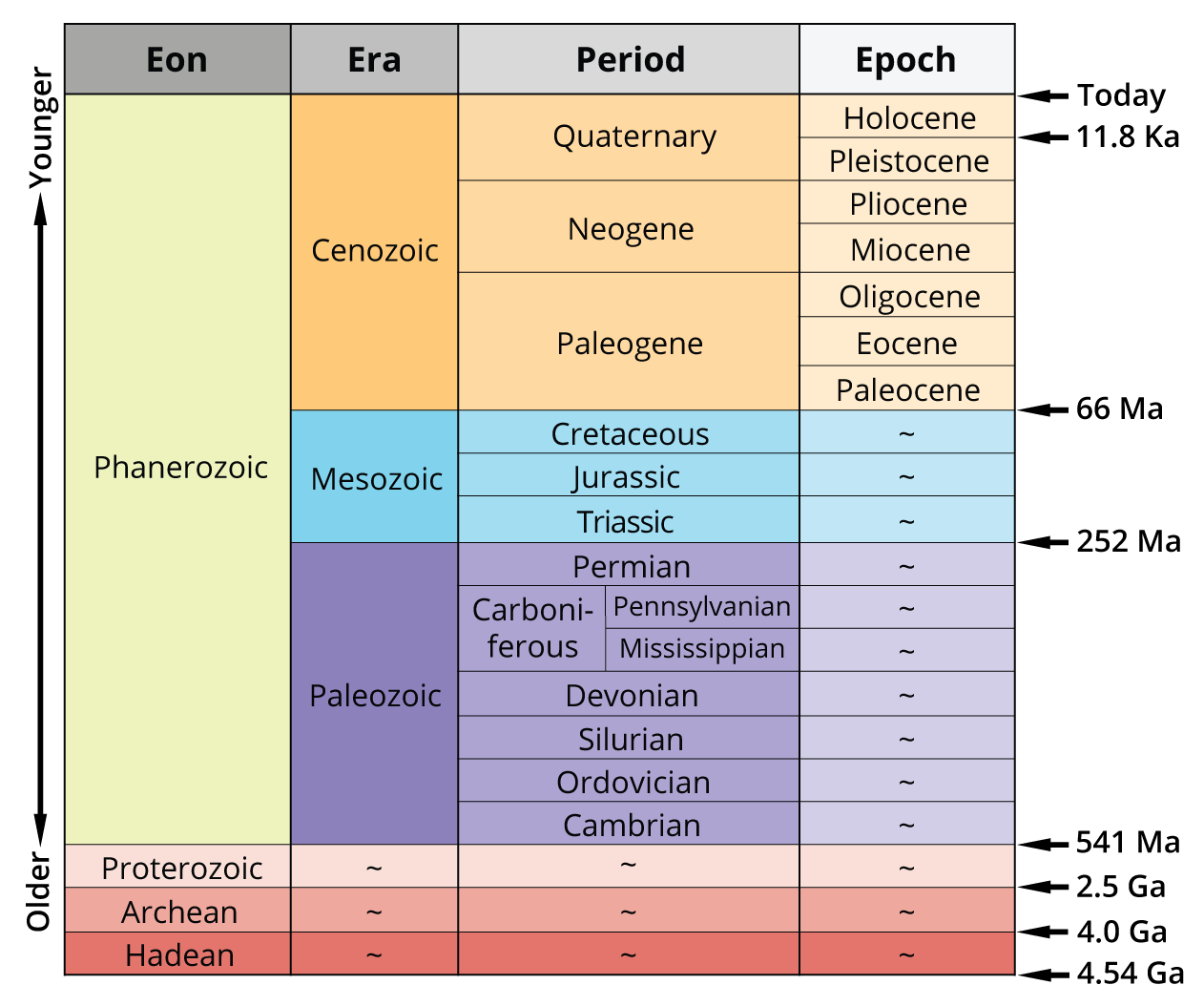

The geological time scale provides crucial context for understanding the magnitude of the Anthropocene proposal. Earth’s 4.54-billion-year history is divided into eons, eras, periods, and epochs based on significant changes recorded in rock layers and fossil records. The Holocene epoch, spanning the last 11,700 years, provided the stable climate conditions that enabled the development of agriculture, cities, and complex human societies. Proposing a new epoch suggests human activities have created changes comparable to natural forces that previously drove geological transitions. courier.unesco+1

The Great Acceleration: Evidence of Planetary-Scale Change

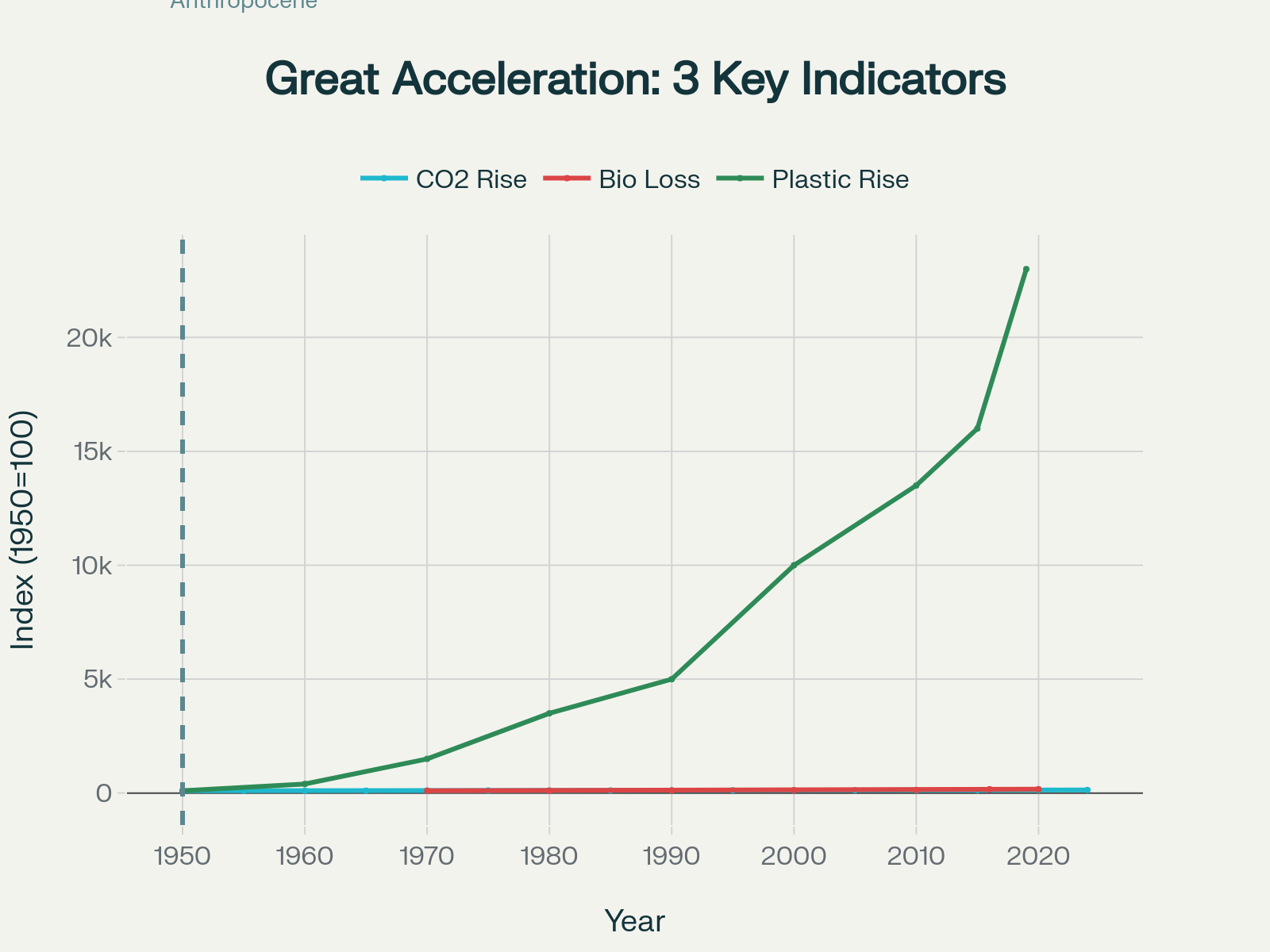

Central to the Anthropocene argument is the concept of the “Great Acceleration”—the dramatic surge in human impact on Earth systems beginning around 1950. This period coincides with unprecedented population growth, industrialization, and resource consumption that has fundamentally altered planetary processes.humanorigins.si+1

The evidence is striking: global population increased from 2.5 billion in 1950 to nearly 8 billion today, while economic activity expanded six-fold. Simultaneously, atmospheric CO₂ concentrations rose from 310 parts per million (ppm) in 1950 to over 426 ppm in 2024—levels not seen for millions of years. This represents three-quarters of all human-contributed atmospheric carbon dioxide.vox+3

Case Study: Crawford Lake and the Nuclear Signature

The Search for a “Golden Spike”

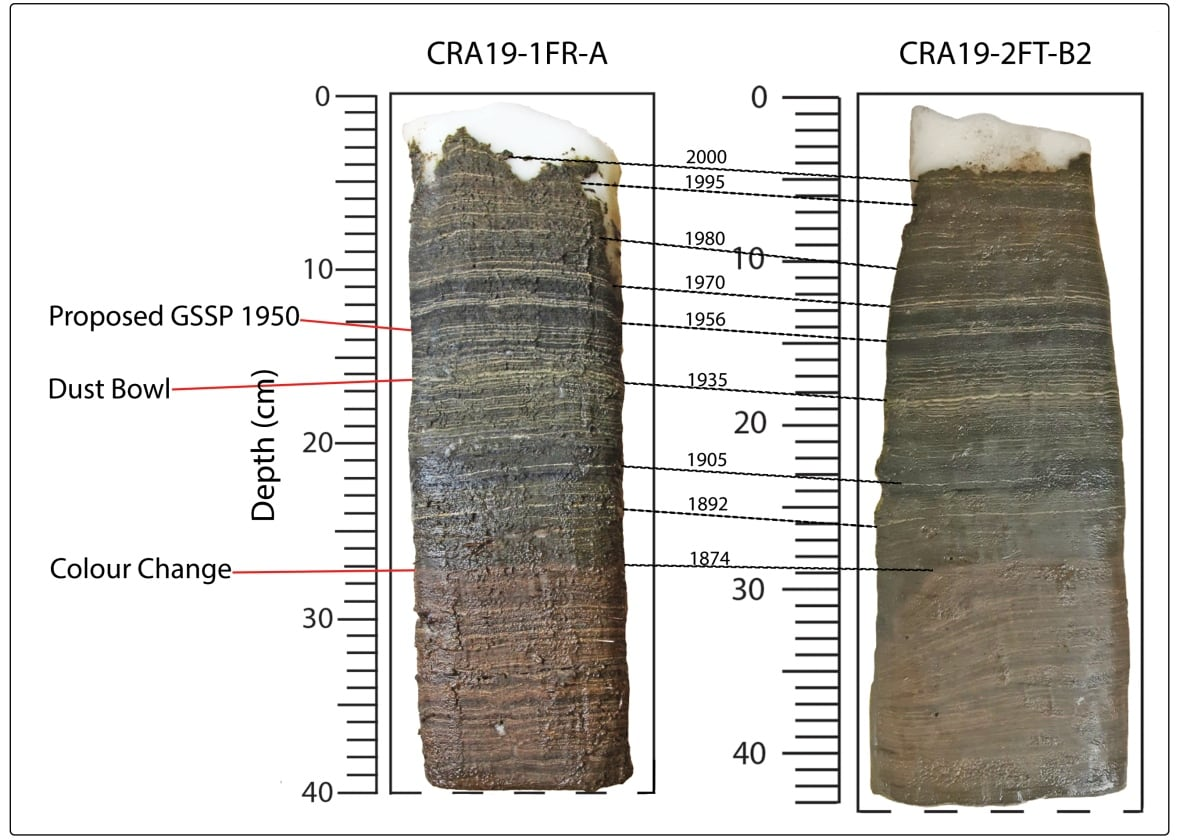

To establish a new geological epoch, scientists must identify a “Global Stratotype Section and Point” (GSSP)—a specific location where rock, sediment, or ice clearly records the transition from one geological period to another. The Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) proposed Crawford Lake in Ontario, Canada, as this crucial reference site.iugs+2

Crawford Lake’s annually-layered sediments provide an exceptionally detailed record of environmental change. The lake’s unique chemistry creates oxygen-poor bottom waters that preserve organic matter and prevent the mixing of sediment layers, creating what scientists call “varves”—distinct annual layers similar to tree rings.anthroecology

Plutonium: The Primary Marker

The AWG identified plutonium isotopes, specifically ²³⁹Pu and ²⁴⁰Pu, as the primary marker for the Anthropocene’s beginning. These artificial radionuclides, created only through nuclear weapons testing and nuclear reactors, provide an unmistakable human signature in the geological record.anthroecology+1

Crawford Lake sediments show a sharp increase in plutonium activity beginning in 1952, coinciding with the first hydrogen bomb tests. Peak activity occurred in 1964-1965, following the Limited Test Ban Treaty that ended atmospheric nuclear testing. This pattern mirrors global fallout records, providing a synchronous marker visible worldwide.wikipedia+1

The nuclear signature extends beyond plutonium. Radiocarbon measurements in Crawford Lake sediments reveal the “bomb pulse”—artificial radiocarbon created by nuclear testing that appears in organic materials globally. Additionally, spheroidal carbonaceous particles (SCPs) from fossil fuel combustion increased twelve-fold in the lake’s sediments during the 1950s.anthroecology+1

Supporting Evidence: A Planetary Transformation

Beyond nuclear markers, Crawford Lake sediments document multiple indicators of human impact:

-

Atmospheric pollution: Dramatic increases in particulates from fossil fuel combustionglobalcarbonproject

-

Agricultural intensification: Rising nitrogen levels from fertilizer usehumanorigins.si

-

Materials revolution: Novel substances including plastics, concrete, and aluminum appearing in sedimentsglobalcarbonproject

-

Ecosystem disruption: Changes in pollen assemblages reflecting land-use modificationsanthroecology

The Scientific Divide: Arguments For and Against

The Case for Recognition

Proponents argue the Anthropocene represents a fundamental shift in Earth system functioning comparable to previous epochal transitions. They point to evidence that human activities have:globalcarbonproject+1

-

Altered atmospheric composition at rates unprecedented in geological historyconsensus

-

Triggered mass extinction with current species loss rates 100-1,000 times higher than natural background ratesoecd+1

-

Modified global biogeochemical cycles through industrial nitrogen fixation and phosphorus mobilizationvox

-

Created novel ecosystems dominated by human-introduced species and materialsanthroecology

Alexander Wolfe of the University of Alberta emphasizes the unique nature of this proposed boundary: “This is the first proposed geological boundary that will have been witnessed directly by advanced human societies. Moreover, it is one that marks the very consequences of these societies’ activities on the planet”.globalcarbonproject

The Opposition’s Concerns

Critics of formal Anthropocene recognition raise several compelling objections:

Temporal Scale Issues

The proposed Anthropocene spans less than 75 years, extraordinarily brief by geological standards. Previous epochs typically last millions of years, raising questions about whether such a short interval merits epochal status.geosociety+1

Stratigraphic Limitations

Some geologists argue the stratigraphic record is insufficient, especially given the recent start date. Philip Gibbard of the University of Cambridge suggests the ‘epoch-division’ is “too large scale when compared to other epochs such as Oligocene or Miocene—which are characterized by a whole series of elements” rather than single markers like radionuclides.iugs+1

Definitional Challenges

The Anthropocene’s beginning remains contested. While the AWG proposed 1952, alternative dates include the Industrial Revolution (late 18th century), the Columbian Exchange (1610), or even the dawn of agriculture thousands of years ago. This lack of consensus complicates formal definition.publicseminar+1

Political Motivations

Some critics question whether the drive for official recognition is “political rather than scientific”. The concept’s popularity beyond geology in fields like environmental policy and social science suggests motivations beyond purely stratigraphic concerns.wikipedia

The March 2024 Decision: Rejection and Response

The Vote and Its Aftermath

In March 2024, the International Commission on Stratigraphy’s Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy voted against recognizing the Anthropocene as a formal geological epoch. The decision was later upheld by the International Union of Geological Sciences, making it official.stratigraphy+1

However, the vote’s validity faced immediate challenges. Martin Head, the subcommission’s second vice-chair, argued there were “statutory violations that call the validity of the vote into question” and that the AWG was not allowed to revise its proposal despite new evidence becoming available.iugs

Implications of Rejection

Despite formal rejection, the scientific community recognizes that the Anthropocene will continue as a valuable concept. The IUGS statement acknowledged: “the Anthropocene will nevertheless continue to be used not only by Earth and environmental scientists, but also by social scientists, politicians and economists, as well as by the public at large. It will remain an invaluable descriptor of human impact on the Earth system”.stratigraphy+1

This distinction between formal geological recognition and conceptual utility highlights the Anthropocene’s broader significance beyond stratigraphy. The term serves as a powerful framework for understanding human environmental impact regardless of its official status.

Global Environmental Data: The Scale of Change

Atmospheric Transformation

The clearest evidence of human planetary impact appears in atmospheric chemistry. Pre-industrial CO₂ levels remained stable around 280 ppm for millennia. Since 1950, concentrations have risen to over 426 ppm today, with growth rates averaging 1.9 ppm annually from 2000-2008. The recent trajectory suggests atmospheric CO₂ could reach 500-600 ppm by century’s end without dramatic intervention.quaternary.stratigraphy+1

This change extends beyond carbon dioxide. Methane concentrations have more than doubled since pre-industrial times, while nitrous oxide levels continue rising due to agricultural practices. The atmospheric chemistry changes of the past 75 years exceed natural variability over millennia.humanorigins.si

Biodiversity Crisis: The Sixth Extinction

Current extinction rates provide perhaps the most troubling evidence of Anthropocene-scale change. The Living Planet Index shows a 68% decline in vertebrate populations between 1970 and 2016. Around one million species currently face extinction, with the global extinction rate at its highest level in 65 million years—at least tens to hundreds of times higher than the natural background rate.humanorigins.si+1

This biodiversity loss, termed the “sixth mass extinction,” differs qualitatively from previous mass extinctions driven by natural catastrophes. The current crisis stems directly from human activities: habitat destruction, overexploitation, pollution, climate change, and invasive species introduction.oecd+1

The Plastics Revolution

Plastic production exemplifies the material transformation characterizing the proposed Anthropocene. From near-zero production in 1950, global plastic manufacturing reached 460 million tonnes by 2019—a 230-fold increase. Only 9% of plastic waste gets recycled, with most ending up in landfills, incineration, or environmental contamination.

Ocean plastic pollution has created entirely novel ecosystems. An estimated 30 million tonnes of plastic waste now contaminate seas and oceans, with an additional 109 million tonnes accumulated in rivers. This plastic legacy will persist for centuries, creating a distinctive stratigraphic marker future geologists could easily identify.

Urbanization and Land System Change

Global urbanization represents another dramatic Anthropocene indicator. Urban population increased from 29% in 1950 to 56% in 2021, with two-thirds of humanity expected to live in cities by 2050. This urban transition has directly affected 83% of Earth’s viable land surface.courier.unesco+2

Cities consume 78% of global energy and produce 70% of greenhouse gas emissions while occupying only 2% of Earth’s surface. Urban expansion drives deforestation, agricultural conversion, and ecosystem fragmentation at unprecedented scales.disaster+1

Policy Implications: Navigating the Planet vs. Profit Tension

Economic Growth in Earth System Context

The Anthropocene debate fundamentally challenges traditional economic models that treat natural resources as infinite inputs for growth. Economist Partha Dasgupta argues that the “explosion of global economic activity following the Second World War coincides with a new geological time” where humans dominate Earth system processes.nature

This coincidence highlights the decumulation of natural capital—wetlands, forests, soils, and ocean systems—that undergirds economic activity. The challenge lies in developing economic systems that operate within planetary boundaries while maintaining human welfare and addressing global inequality.nature

Business Accountability in the Anthropocene

The recognition of human planetary impact, whether formally acknowledged or not, raises profound questions about business responsibility. Four major lines of thinking emerge for reconsidering corporate accountability in the Anthropocene context:globaia

Rethinking Business Purpose: Moving beyond shareholder primacy to consider planetary impacts as core business concerns.

Expanded Accountability: Acknowledging companies’ shared responsibility for production activities’ environmental consequences throughout supply chains.

Enhanced Liability: Heightening collective and individual liability for actions that contribute to exceeding planetary boundaries.

Political Responsibility: Recognizing business accountability for influencing political processes that affect environmental governance.

Governance Challenges

The Anthropocene concept highlights the inadequacy of existing governance systems designed for a stable Holocene world. Earth system governance research emphasizes the need for “interrelated and increasingly integrated systems of formal and informal rules, rule-making systems, and actor-networks at all levels” to address planetary-scale challenges.eos+1

Key governance challenges include:

-

Scale Mismatches: Local institutions managing global problems

-

Temporal Misalignments: Short political cycles addressing long-term environmental changes

-

Knowledge Integration: Combining scientific evidence with policy implementation

-

Justice and Equity: Ensuring fair distribution of environmental costs and benefits

Policy Innovation Requirements

Effective environmental policy in the Anthropocene requires institutions that can:

Utilize Dispersed Knowledge: Harnessing local information about environmental change

Adapt to Uncertainty: Adjusting policies as scientific understanding evolves

Coordinate Across Scales: Linking local actions to global impacts

Address Equity: Ensuring just transitions that don’t burden vulnerable populations

The Planet vs. Profit Paradigm

Historical Context of Sustainability

Throughout the Anthropocene period, sustainability concepts have consistently grappled with treating “nature as resource” while linking “sustainable practices to profit-making”. This tension reflects deeper questions about whether market-based approaches can address planetary-scale environmental challenges. bbc

The Brundtland Commission’s “Our Common Future” report marked a crucial shift from “protecting nature against humans” to “protecting nature to promote human development”. While this approach enabled more ambitious international policies, it maintained an instrumental view of nature’s value primarily serving human interests.atlanticcouncil

Market Solutions and Limitations

Market-based environmental policies offer advantages in harnessing private knowledge and incentives for environmental improvement. Well-functioning markets can drive innovation in clean technologies, efficient resource use, and pollution reduction. Carbon pricing, renewable energy markets, and ecosystem service payments demonstrate market potential for addressing environmental challenges.

However, market solutions face inherent limitations in addressing Anthropocene-scale challenges:

-

Temporal Mismatches: Market time horizons often prove too short for long-term environmental stability

-

Scale Problems: Local market failures accumulate into global environmental crises

-

Equity Issues: Market solutions may exacerbate environmental injustices

-

Value Limitations: Many ecosystem services remain difficult to price accurately

Alternative Economic Models

Growing recognition of market limitations has spurred interest in alternative economic approaches:

Circular Economy: Designing out waste and pollution while keeping materials in productive use

Degrowth: Questioning whether infinite growth is compatible with finite planetary resources

Regenerative Economics: Economic models that restore rather than deplete natural systems

Commons-Based Approaches: Collaborative governance of shared environmental resources

Looking Forward: Implications for Environmental Responsibility

The Anthropocene as Framework

Whether or not the Anthropocene gains formal geological recognition, it provides a powerful framework for understanding humanity’s environmental impact. The concept helps integrate scientific evidence of planetary change with policy responses and public awareness.

The Anthropocene narrative emphasizes several key insights:

-

Human Agency: People have become the dominant force shaping planetary evolution

-

System Interconnections: Local actions now have global environmental consequences

-

Temporal Responsibility: Current decisions affect Earth’s trajectory for millennia

-

Collective Challenge: Addressing planetary change requires unprecedented cooperation

Pathways to Planetary Stewardship

The Anthropocene concept calls for a transition from inadvertent planetary impact to conscious “planetary stewardship”. This shift requires: eos

Scientific Integration: Combining Earth system science with social science to understand human-environment interactions

Institutional Innovation: Developing governance systems capable of managing planetary-scale challenges

Technology Deployment: Scaling clean energy, sustainable agriculture, and industrial processes

Social Transformation: Changing consumption patterns, urban design, and economic priorities

Global Cooperation: Coordinating action across nations, sectors, and scales

The Role of Economic Systems

Successfully navigating the Anthropocene requires economic systems that operate within planetary boundaries while promoting human welfare. This transition involves: nature

-

Natural Capital Accounting: Incorporating ecosystem services into economic decision-making

-

Long-term Value Creation: Extending investment horizons to match environmental timescales

-

Circular Design: Eliminating waste through closed-loop production systems

-

Regenerative Practices: Economic activities that restore rather than degrade ecosystems

Conclusion: Defining Our Geological Legacy

The Anthropocene debate represents more than a scientific classification dispute—it embodies humanity’s struggle to understand and respond to our role as a planetary force. While formal geological recognition was rejected in 2024, the evidence of human planetary impact remains undeniable. stratigraphy+1

The concept’s enduring value lies not in stratigraphic classification but in its capacity to frame urgent environmental challenges. Whether we call it the Anthropocene or continue recognizing the Holocene, the reality remains: human activities have altered Earth systems at scales and speeds unprecedented in human history.

The “Planet vs. Profit” tension at the heart of this debate reflects deeper questions about sustainable development in an era of planetary boundaries. Moving forward requires economic and governance systems that recognize natural limits while promoting human flourishing within those constraints.

As we continue deeper into what many scientists recognize as the Anthropocene, the challenge lies not in geological nomenclature but in developing the institutional, technological, and social innovations necessary for planetary stewardship. The debate itself demonstrates humanity’s growing awareness of our geological significance—a crucial first step toward taking responsibility for our planetary legacy.

The stakes could not be higher. As the scientific community noted, “we risk driving the Earth System onto a trajectory toward more hostile states from which we cannot easily return”. Whether formally recognized or not, the Anthropocene challenges us to become conscious stewards of the only planet we have

Leave a Reply